Dr Sallie BurroughResearch Fellow, Science Communicator, Exhausted Parent. Telling it how it is. I didn’t notice how much plastic was in my life until I had children, then suddenly, a growing stash of brightly-coloured, petroleum-based paraphernalia made me feel like the mere existence of my offspring was enough to support a small petrochemical plant. To be clear, some of this I merrily and unthinkingly purchased – plastic baby bottles, children’s cups, baby baths, car seats, change mats, a safari animal themed mobile. The list was long. Much was also thrust upon us by well-meaning relatives whose motive in showering us with plastic playthings was wholeheartedly the happiness of my kids. I don’t blame them, it’s hard to find alternatives - plastic toys, which are notoriously difficult to recycle, account for 90% of the toy market, largely because they are inexpensive to produce. I get it, the unquestionable joy on a child’s face after handing them a gift creates treasured moments for grandparents, friends and family whose brief encounters with my children lead them to believe that their gift has left nothing but lasting happiness in my home. What I have learnt as a parent however, is that the much coveted plastic monstrosity is, more often than not, discarded more rapidly than a rocket-full-of-monkeys. Kids are fickle creatures and there is well-documented evidence that the more toys they have, the less they play with them. It’s not just Nana and Gramps – plastic comes at my kids from every direction, it’s in gift bags at parties, on magazines, inside cereal boxes. @CBeebiesHQ magazine - I’m talking to you, we love your mags but we don’t want your gimcrack plastic debris stuck to the front. I’m also not immune to pre-schooler pressure and will climb down from my high-horse to admit that this year, I caved when eBay couldn’t provide the preloved version of a much coveted plastic archaeologist doll. But the momentary joy of its acquisition, wasn’t priceless. My daughter, like many others, will pay for our birthday gift choices in the world she will inherit. The irony of my plastic archaeology friend is that she was loved for a full 72 hours before being unceremoniously relegated to the murky depths of the toybox. Nonetheless, she will remain with us on Earth for another 500 years. Where exactly, archaeo-doll will eventually end up is hard to say - languishing in the ever expanding landfill? floating amongst the 150 million tonnes of plastic that circulate in our oceans? The scale of the plastic pollution problem was famously catapulted into public consciousness in 2016 when David Attenborough directed his weighty influence on to the issue in Blue Planet II, but our plastic predicament is neither new nor unpredicted. Arguably, we slept-walked into the crisis, guided by action and inaction that was shaped by corporate campaigns. Investigative studies have found good evidence that industry leaders pre-empted regulatory action by pushing recycling as a solution whilst being fully cognizant of its infeasibility as a viable economic solution. They weren’t wrong – less than 10% of all plastic has ever been recycled in the last 40 years. Since my childhood, plastic production has doubled every decade, my car is built out of it, my clothes are made from it, it’s in my teabags. Its inexpensive, mind-boggling ubiquity has defined the throwaway, convenience-is-king culture that pervades this century. Covid has contributed to the problem, not just in terms of adding facemasks to the debris. In both Europe and the US, plastic industries used the pandemic to attempt to delay plastic regulations and in the latter case solicited an official declaration of support for single-use plastic products as ‘the sanitary choice’, despite the lack of scientific evidence to support that claim. Similarly, supermarkets put pressure on the UK government to pause or postpone the implementation of deposit return systems (DRS) due to come into force in 2023, with the wholly unsubstantiated claim that such schemes would be a breeding ground for the virus. As our oceans choke with lego star-wars ships, plastic dolls and carrier bags, the scientific community has understandably focused its fastidious eye on how these alien objects have affected marine ecosystems, not least as these plastics break down into tiny particles and constitute chemical additives. They’ve accumulated in the food chain, in the water, in the air we breathe; they end up inside us. There is a growing body of research tackling the challenging issues around what that means for human health. Everything from the impact of chemical additives like BPA and toy-softening Phthalates (the latter now banned from children’s toys) to the physical interaction of nanoplastics with our cells, remains poorly understood. Most scientific studies still frame microplastic risks as hypothetical, while 24% present the risks to human health as well established. Regulation trudges reluctantly along the same path as scientific progress but there is an awful lot we don’t yet understand about the health implications of where all those plastic chemicals go. With those uncertainties and my love of turtles in mind, I will try, all be it with some futility, to avoid plastics where possible. In my new role as killjoy for my children’s highly marketed-to brains, here’s some other stuff I know they will love just as much as archaeo-doll’s latest ballerina cousin:

4 Comments

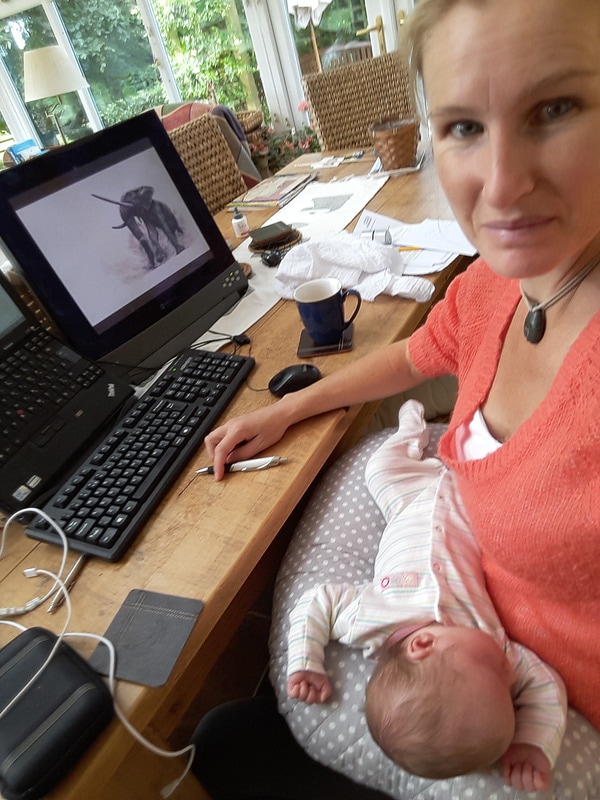

When I was a 20-something year old starting out on my academic journey, I had an odd conversation about babies. In it, a Professor bemoaned a female colleague as "one of those feminist-types” insistently vocal about the difficulties of combining motherhood with academia. "Good scientists", he commented, "would just get on with it and let their own merit speak for itself". I don't think I had much of an opinion back then, but I didn't stick my neck out and disagree. These days I find myself "one of those" and like so many merited females that have bumped along this unmetalled road, am having a hard time leaving it to my merit to do the talking. HESA's[1] 2016/17 figures suggest that while a sizeable 46% of all academic staff in the UK were female, something was still disproportionately preventing them or dissuading them from making it through the system, with only 25% of professors being women. Why? A study by Georgina Santos in 2019 found a negative link between being a woman and the likelihood of being employed at a senior level within Russel group universities, irrespective of childcare responsibilities. The gender gap is real and still to be bemoaned but research also shows that mothers (both inside and outside academia) tend to be seen as less competent, less committed, less likely to be hired and often have lower starting salary recommendations compared to non-mothers (Corell, Benard, and Paik 2007; Cuddy, Fiske and Glick 2004). Add to that the “career scar" encumbered from not having the time to apply for grants and fellowships, the penalties of lower productivity in terms of publication rate; the much decreased access to networks, collaborations and new discoveries bound into the childcare-conference conundrum and the decreased mobility that limits access to the hyper-niche job market that is international science. Suddenly, the price of parenthood, of part-time work and maternity leave seems intimidatingly steep. Indeed, a number of studies have found that academic women and women in science are more likely to be successful if they strategically delay or forgo marriage and children. Data from the US suggests that only one in three women who accepts a fast-track university job before having a child ever becomes a mother (Williams and Ceci, 2012) and among tenured faculty, 70 percent of men are married with children compared with 44 percent of women (Mason, Wolfinger and Goulden, 2013) I was neither savvy nor strategic about children. My timing was terrible and I find myself in the quagmire of these apparently insoluble issues. I struggle to keep my head above the academic water which, in science, flows fast and cares not that I am temporarily weighted down by 3pm pickups and night feedings. I have had to stomach colleagues “borrowing” my scientific ideas and running with them whilst I am incapacitated by the stringent time-constraints of tiny children. I have had to dispense with ego and pride and perfectionism. And because my planning was bad, I have found myself in limbo, too senior to apply for 99% of grants, still too precarious not to. But motherhood has taught me valuable lessons contrary to all the assumptions bound into our unconscious bias. Motherhood in all its wonderous, exhausting manifestations has schooled me in fortitude, patience and resilience. It has, with exquisite clarity, revealed my ability to endure more shit (metaphorically and literally) than I ever imagined possible. You can load me high and heavy with deadlines and the bottomless neediness of tiny humans and, while I might be a little less fleet-of-foot, I generally won’t let you down. I have learnt to be 100 times more efficient in my meagre work hours than my former self. I have learnt that you can deprive me of sleep for days, weeks, months on end, suck every last ounce of solitude and social life out of my chaotic existence but I will steadfastly continue to deliver food, silliness and love to the living room, papers to the publishers, data to the desks that need it and lectures to the teaching rooms. You can watch me squeeze the work of 2 full time jobs into a precarious part-time post and still make it to the nursery gates on time. You can judge me, exclude me, laugh at me if you like, god help us if we can’t find the funny side of life with tiny, unreasonable humans. There will never be another point in life where so many people have asked so much of me. Nothing you can throw at me in the workplace will ever be harder than these few years spent spinning 1000 plates whilst walking the tightrope across toddlerdom to reclaim the identity of the woman I left behind. Like so many other mothers negotiating work life in ‘the hood’ I have learnt the hard way what resilience really means. I have learnt that efficiency and empathy, competence and warmth, are not mutually exclusive. It seems to me that when mothers do finally return to the workforce full-throttle they are more, not less, valuable than their non-parent colleagues and, it turns out, I’m not wrong. In a study of over 3000 women and men across a diverse employment landscape, women appear to contribute 10% more than their male colleagues. A separate study found that over the course of a 30-year career, mothers outperformed women without children at almost every stage of the game. In fact, mothers with at least two kids were the most productive of all. These problems are not unique to academia or to science, but these are industries at the forefront of forging the minds of future generations, it matters that we get this right. Despite the progressive, pioneering position academia makes claim to as it strives to solve the biggest of societies problems, it is struggling to resolve its own hang-ups. The attitude of that Professor, now rarely uttered out-loud, is deeply embedded within the institutional infrastructure. Manoeuvring one of the worlds most intensely competitive systems towards a framework that allows time-out without penalty, will not be easy. As a community we have already recognised that motherhood knocks huge holes into the research-professor pipeline, that the difficulties faced when raising young families ‘drive women out of scientific careers for which they are trained and in which they would be as successful as men were they to make the choice not to have kids’ (Williams and Ceci, 2012). But I still don’t see the part-time Associate Professor jobs. There is little in the way of substantial policies and funding for women to ‘catch up’ when they return to work. I don’t know of a single job-share academic post in my field despite the benefits to retaining women in senior leadership roles. From a personal perspective, one thing is clear, wherever I choose to go next, know that I will not sit quietly with my merits. I know their strengths, they are many, and when I’ve crossed this tightrope they may speak for themselves again but until then, I’ll take the risk of being judged to shout loudly from the highwire in the hopes that things might be different for my daughters. [1] Higher Education Statistics Authority image from here

In my 'spare' time I'm climbing a steep learning curve at UWE in Bristol doing a part-time MSc in Science Communication. This is one of my assignments, 2000 academic words on a scientific controversy, a (pre-covid) summary of why its so difficult to initiate action on climate change and how we might do better as communicators. Already out of date, the world is now a different place and there is so much more to say on this, just too little time in my locked-down life with tiny children to articulate it right now. But, perhaps as we move forward from Covid, it might serve as a modicum of use in distilling some of the underlying issues that seem to persistently paralyse meaningful political action on what will likely be the defining issue of our children's lives. The emergency that wasn’t: cultural cognition and the politicisation of climate science.

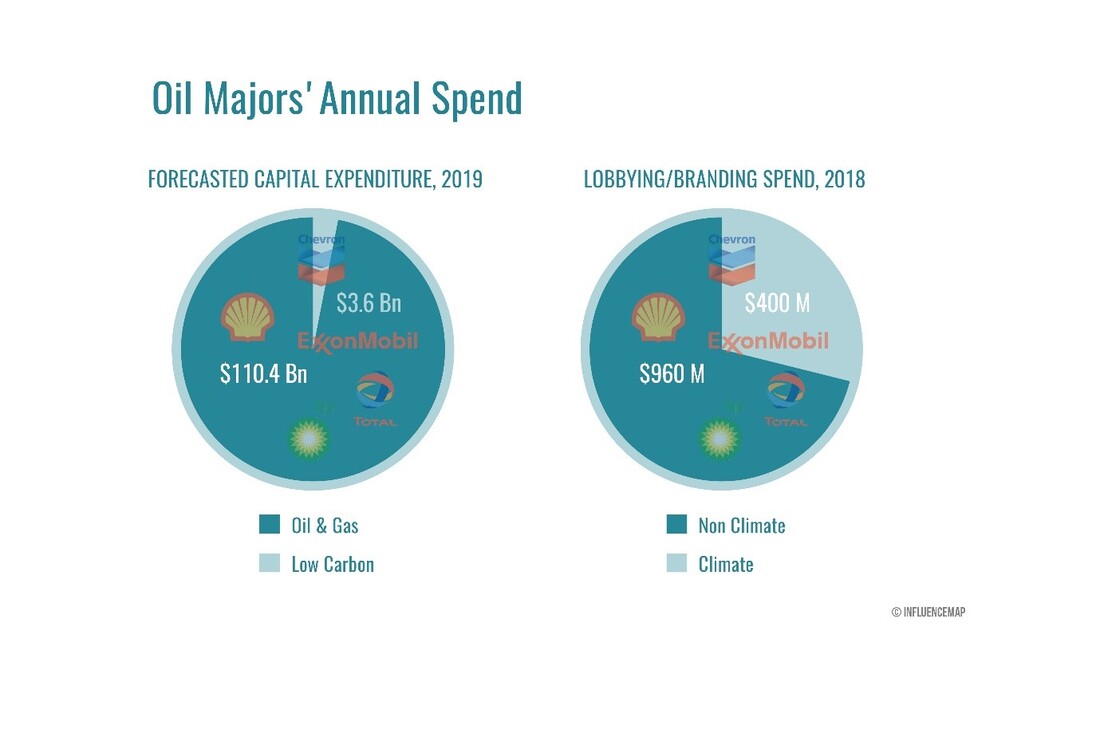

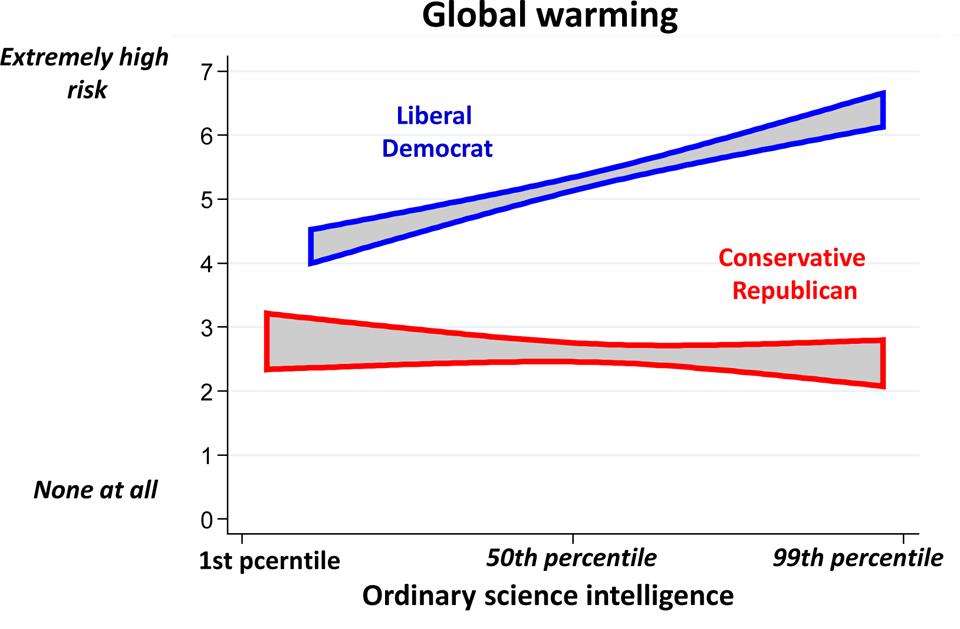

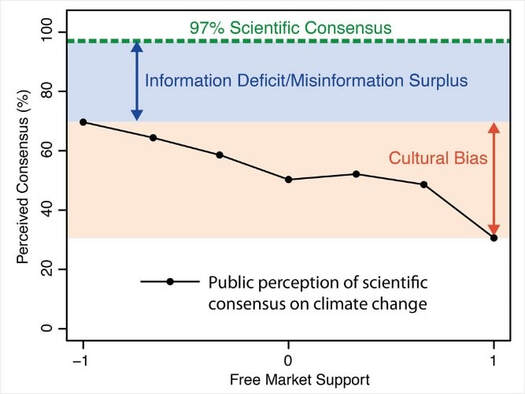

Introduction Both the evidence for anthropogenic climate change and the dialogue between science, the public and politics has increased steadily since the late 1970s. By contrast, controversy within the scientific discourse has substantially diminished as increased technological capability, notably computing power, has reduced uncertainties. By the early 2000s, little scientific disagreement remained (Oreskes, 2004). More than 97% of actively publishing climate scientists concur that climate-warming and other climate changes during the past century are due to anthropogenic transfer of carbon stocks from the ground to the atmosphere (Cook et al., 2013, 2016) and nearly all the leading scientific organizations worldwide have issued public statements endorsing this position. Over the last 30 years calls by scientists to curb CO2 emissions have been ardently repeated, not least through the mechanisms of the 1992 Rio Summit, the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, and the 2015 Paris Agreement (Ripple et al., 2017). But despite political commitments, emissions have continued to increase. Responsively, the scientific message has grown louder, more urgent and emotive. In its most recent scientific Special Report, the IPCC[1] concluded “Limiting global warming to 1.5oC would require rapid, far-reaching and unprecedented changes in all aspects of society” and in 2019, 11,000 scientists endorsed an article published in the journal BioScience, stating “We declare..unequivocally that planet Earth is facing a climate emergency… a sustainable future…entails major transformations in the ways our global society functions.” (Ripple et al., 2019; IPCC, 2018). The emotive urgency of the scientific message has been echoed and bolstered by a visible subset of the public, particularly the youth, via campaigns such as Extinction Rebellion and Greta Thunberg's School Strike for Climate movement. Against this backdrop of overwhelming consensus and urgency, how is it that the science of climate change has consistently remained, at least politically, one of the most controversial scientific issues of our time? Knowledge deficit and distortion and the rise of neoliberalism Historically, the conventional explanation for the controversy has emphasized a sceptical public, distrustful of scientific findings due to i) a deficit of understanding about the science of climate change and science more generally (Miller, 2001) and ii) the exploitation of this knowledge deficit through the deliberate distortion and politicisation of scientific information. As Lenzi (2019) points out, the very epistemology of science: its openness to challenge and revision and its transparency on quantifying uncertainty, is frequently misunderstood to mean the science of climate change is ambiguous. It is in this philosophical gap, that the deeply embedded power of the fossil fuel industry (Oreskes and Conway, 2010; Weber and Stern, 2011); political/financial short-termism and media-bias has flourished (Gunningham, 2019). Leaked documents have frequently revealed deliberate strategies by fossil fuel interests to locate ‘expert’ sceptics, identify thinktanks and media moguls that would question the scientific consensus of anthropogenic climate change. The five largest publicly-traded oil and gas companies (ExxonMobil, Royal Dutch Shell, Chevron, BP and Total) invested ~$1Bn during the 3 years following the 2015 Paris Agreement on misleading climate-related branding and lobbying (InfluenceMap, 2019). This spend (mostly targeted at delaying, blocking or controlling climate related policy) sits alongside careful campaigns of positive decarbonisation messages with an apparent goal to maintain public support whilst simultaneously holding back binding policy via direct lobbying and the funding of sympathetic thinktanks. A successful tactic of the “climate change denial countermovement” (Dunlap and McCright, 2015) has been to shift from questioning scientific consensus to denigrating the urgency of its findings, using language such as ‘climate alarmists’ alongside describing themselves as ‘sceptics of climate catastrophism’ and/or highlighting the economic costs of mitigation (Dunlap, 2013; Kasser et al., 2009). Fig 1: Oil and gas company spend on low carbon investments vs fossil fuel investments (left) and spend on pro-climate branding/lobbying vs opposing binding climate policy (right) (InfluenceMap, 2019). Between 2006-2010 UK political parties were more progressive than the public utilising preference shaping over preference accommodation when it came to the public’s views on climate change (Carter, 2014). The decarbonisation of the economy is, however, particularly vulnerable to increasing right-wing populism and post-truth politics since its success is ultimately determined by market implementation and socio-political processes (Fraune and Knodt, 2018). Reflecting these trends, recent years have seen right-of-centre parties becoming retrogressive in their response to climate science. Since 2015, despite commitments to being the ‘greenest government ever’, the Conservative government dismantled climate initiatives implemented in the preceding decade including solar power subsidies, incentives for low-emission vehicles and the zero-carbon homes plan (Lawrence et al., 2019). This mirrored a strengthening of neoliberal economic ideas favouring free market deregulation, a trend strongly influenced by right-wing thinktanks such as the Legatum Institute and the IEA[2], whom have also published material questioning climate-science findings. Whilst thinktanks have always played an important part in shaping UK government policy, the growing number of connections between the Conservative government and ultra-free market thinktanks has grown substantially in the last decade (Plehwe, 2014). More recently the political left have advocated for strong state intervention to support climate change mitigation under a pro-scientific banner. Polarisation has ensued. In an analysis by CarbonBrief on parliamentary reference to climate change, Labour, the Liberal Democrats, the Greens and the SNP collectively racked up 339 references to a climate “crisis”, “emergency” or “catastrophe”, the Conservatives have only used these terms 32 times (Gabbattis and Tandon, 2019). The same report found that while 576 MPs use twitter, only 64 of them (12%) follow climate scientists, of which 42 are Labour MPs. Funded by donations from fossil fuel magnates, billionaires and oil companies, international umbrella organisations such as the Atlas network deliberately strategize to multiply the number of neoliberal thinktanks, providing an impression of widespread support for fringe climate-science views subsequently echoed in media outlets. This multiplication effect is amplified in new media, the content distribution of which is interminably scalable. In an analysis of the digital footprint of 386 climate change sceptics with the same number of expert scientists, Petersen et al., (2019) found that the former were featured in 49% more digital media articles than scientists. Capable of tailoring newsfeeds to preferences and prejudices, social media platforms then disproportionately replicate highly politicised, or misleading information, creating so-called ‘echo chambers’ which insulate individuals from exposure to alternative views, accentuating polarisation. Cultural bias and the politicisation of public opinion As political polarisation of climate-science has grown, embedded value-bias has increasingly influenced the interaction of publics with media-messaging on climate-change. Empirical evidence drawn from US studies suggests ‘belief’ in high-risk anthropogenic climate change is a stronger indicator of an individual’s left-right (liberal-conservative) leaning than any public deficiencies in science education (Kahan, Jenkins-Smith and Braman, 2011). These data bear out the predictions of ‘cultural cognition theory’ which argues that individuals selectively assess risk in ways that draw on shared values within their own cultural group (Kahan et al., 2011). Political polarisation of the public, reflects a gradation between egalitarian communitarian values on the left (perceive less rigid social organisation, favour collective action and state intervention) and hierarchical Individualists on the right (tie authority to social ranking, disapprove of collective interference with individual actions). The more an individual endorses the latter, the more they are likely to downplay the risks highlighted by climate change science (Kahan et al., 2012, 2011). Fig 2: Risk perception of climate change, science literacy (Ordinary Science Intelligence) and political identity. N =1800, April-May 2014. Shaded areas represent 0.95 confidence intervals (Kahan, 2015). Evidence suggests the UK public also interpret information and expertise in partisan ways that similarly reflect their political ideology (Clements, 2012; Poortinga et al., 2011; Whitmarsh, 2011). While UK public opinion polls record a significant jump in general public consensus over the last year with 80% of the public in March 2019 indicating they were fairly concerned (45%) or very concerned (35%) about climate change (BEIS, 2019), the weight of opinion on the risk-severity has a clear cultural influence with 64/59% of Labour/Liberal Democrat supporters saying they are very concerned, compared to 42% Conservative supporters. Similarly, 70/69% of Labour/Lib Dem supporters believe the UK should achieve net zero emission more rapidly than by 2050, compared to 37% of Conservative supporters (Dickman and Skinner, 2019). Produced and reinforced by political polarisation, demands for political/societal response on the left have grown in effectiveness. Extinction rebellion and global climate strikes have employed deliberate strategies of civil disobedience to push for action that unites behinds the science. Such non-violent movements arguably need only 3.5% of the population to mobilise (Chenoweth and Stephan, 2011) to reach a social tipping point (Gladwell, 2000) stimulating governmental response. In the UK, the latter has included 2 parliamentary debates and the declaration of a ‘climate emergency’ (Gunningham, 2019) but whether or not policy commitment meets the demand for real action from these (dominantly left-wing) public voices under an increasingly right-wing government is yet to be seen. Interestingly, empirical data (Kahan, 2015) also suggest that contrary to the ‘deficit model’ of society’s engagement with science, the greater an individual’s level of scientific education/comprehension, the more polarised their views on the risk of climate-change become (fig 2). This reflects a greater aptitude, when faced with cognitive dissonance, to search out or restructure information to support an individual’s cultural predisposition (Lewandowsky et al., 2012), a process facilitated by the era of unchecked new media and post-truth politics. Cook et al., (2017) have argued that an information deficit, or more likely, a misinformation surplus, accounts for a proportion of the gap between scientific and public views after the effects of cultural bias have been accounted for (fig 3). But Kahan (2015) and others argue that public messaging on climate change that endeavours merely to fill the deficit, or which is guilt or fear-based (e.g. in relation to consumerism) (Corner, Markowitz and Pidgeon, 2014) unintentionally accentuates the controversy by predisposing individuals to view climate-change mitigation as a direct attack on their identity and values (Nilsson, von Borgstede and Biel, 2004). Fig 3: Impact of political values on public perception of climate change consensus in the US. N = 200, 2013 (Cook, 2014) In line with new norms in science communication that embrace dialogue, consultation and participation (Wilkinson and Weitkamp, 2016), deliberation may offer the best chance of alleviating controversy from climate change mitigation policies (Niemeyer, 2014; Hobson and Niemeyer, 2011). Deliberative public consultation in Ireland involving 99 randomly selected Irish citizens, resulted in consensus support for 13 Irish assembly proposals to tackle climate change including those (e.g. higher taxes) thought to be politically infeasible (Lenzi, 2019). The success of such initiatives lies in kerbing cultural bias through establishing community cohesion. Dryzek, (2009) argues that these deliberative norms need to be engendered within society more broadly but up-scaling the deliberative process, is not fast or straightforward.

Others (e.g. Kahan, 2015; Lenzi, 2019) suggest de-escalating the polarisation that props up the controversy gap between mitigation-commitment and real action requires some form of ‘nudging’. Nudge-theory endeavours to steer individuals in particular directions by accepting “the cognitive architecture of choice that faces citizens and work with – rather than against – the grain of biases, hunches and heuristics” (John, Smith and Stoker, 2009, p.363). E.g. ‘Identity affirmation’, avoiding messaging that forces individuals to choose between their cultural identity and what is known by science (Kahan, 2015) is achieved by reframing the issue. Examples include highlighting the capability of human ingenuity via geoengineering/technological solutions or emphasising the possibility of ‘stranded assets’ under free market economics. Ensuring ‘pleuritic advocacy’ i.e. diversity of cultural values among communicators and experts, also renders information less easily rejected (Lenzi et al., 2019). Conclusion The science of climate change has entered a spiral of politicization and scientists themselves are increasingly becoming ‘political actors’ (Dryzek, 2011). In the UK, the controversy of climate science has moved beyond consensus-debate towards questioning the risk-magnitude and/or mechanisms of mitigation. Fuelled by strategic campaigns by fossil fuel interests and neoliberal thinktanks (Oreskes and Conwy, 2010; Weber and Stern, 2011) funded by those with vested interests in a deregulated economy, political and cultural factionalization has grown. Polarised public opinion on climate change science, finds its roots not in ‘scientific illiteracy’ but in value-laden political predispositions. Alleviating the public and political polarisation that impedes action on climate change (as witnessed at COP25) requires a tranche of approaches from science communication professionals including increasing public engagement in deliberative processes and protecting citizens from having to choose between scientific knowledge and their own cultural/political identities within society. Without these, “rapid, far-reaching and unprecedented changes in all aspects of society” will remain an unlikely mitigation outcome. References BEIS (2019) BEIS Public Attitudes Tracker review (Wave 29). Chenoweth, E. and Stephan, M. (2011) Why civil resistance works: The strategic logic of nonviolent conflict. New York: Columbia University Press. Clements, B. (2012) The sociological and attitudinal bases of environmentally-related beliefs and behaviour in Britain. Environmental Politics. 21 (6), pp. 901–921. doi:10.1080/09644016.2012.724215. Cook, J. (2014) Why we need to talk about the scientific consensus on climate change | John Cook | Environment | The Guardian. The Guardian Cook, J., Lewandowsky, S. and Ecker, U.K.H. (2017) Neutralizing misinformation through inoculation: Exposing misleading argumentation techniques reduces their influence. PLoS ONE. 12 (5), . doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0175799. Cook, J., Nuccitelli, D., Green, S.A., Richardson, M., Winkler, B., Painting, R., Way, R., Jacobs, P. and Skuce, A. (2013) Quantifying the consensus on anthropogenic global warming in the scientific literature. Environmental Research Letters. 8 (2), . doi:10.1088/1748-9326/8/2/024024. Cook, J., Oreskes, N., Doran, P.T., Anderegg, W.R.L., Verheggen, B., Maibach, E.W., Carlton, J.S., Lewandowsky, S., Skuce, A.G., Green, S.A., Painting, R. and Rice, K. (2016) Consensus on consensus: A synthesis of consensus estimates on human-caused global warming. Environmental Research Letters. 11 (4), . doi:10.1088/1748-9326/11/4/048002. Corner, A., Markowitz, E. and Pidgeon, N. (2014) Public engagement with climate change: the role of human values. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change. 5 (3), pp. 411–422. doi:10.1002/wcc.269. Dickman, A. and Skinner, G. (2019) Concern about climate change reaches record levels with half now ‘very concerned’ | Ipsos MORI Ipsos MORI Political Monitor. Dryzek, J.S. (2009) Democratization as deliberative capacity building. Comparative Political Studies. 42 (11), pp. 1379–1402. doi:10.1177/0010414009332129. Dunlap, R.E. (2013) Climate Change Skepticism and Denial: An Introduction. American Behavioral Scientist. 57 (6), pp. 691–698. doi:10.1177/0002764213477097. Dunlap, R.E. and McCright, A.M. (2015) Challenging climate change: the denial countermovement. Climate Change and Society: Sociological Perspectives. pp. 300–332. Fraune, C. and Knodt, M. (2018) Sustainable energy transformations in an age of populism, post-truth politics, and local resistance. Energy Research & Social Science. 43 pp. 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2018.05.029. Gabbattis, J. and Tandon, A. (2019) Analysis: The UK politicians who talk the most about climate change. Gladwell, M. (2000) The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. Gunningham, N. (2019) Averting Climate Catastrophe: Environmental Activism, Extinction Rebellion and coalitions of Influence. King’s Law Journal. 30 (2), pp. 194–202. doi:10.1080/09615768.2019.1645424. Hobson, K. and Niemeyer, S. (2011) Public responses to climate change: The role of deliberation in building capacity for adaptive action. Global Environmental Change. 21 (3), pp. 957–971. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.05.001. IPCC (2018) IPCC, 2018: Summary for Policymakers. John, P., Smith, G. and Stoker, G. (2009) Nudge nudge, think think: Two strategies for changing civic behaviour. Political Quarterly. 80 (3), pp. 361–370. doi:10.1111/j.1467-923X.2009.02001.x. Kahan, D.M. (2015) Climate-science communication and the measurement problem. Political Psychology. 36 (S1), pp. 1–43. doi:10.1111/pops.12244. Kahan, D.M., Jenkins-Smith, H. and Braman, D. (2011) Cultural cognition of scientific consensus. Journal of Risk Research. 14 (2), pp. 147–174. doi:10.1080/13669877.2010.511246. Kahan, D.M., Peters, E., Wittlin, M., Slovic, P., Ouellette, L.L., Braman, D. and Mandel, G. (2012) The polarizing impact of science literacy and numeracy on perceived climate change risks. Nature Climate Change. 2 (10), pp. 732–735. doi:10.1038/nclimate1547. Kahan, D.M., Wittlin, M., Peters, E., Slovic, P., Ouellette, L.L., Braman, D. and Mandel, G.N. (2011) The Tragedy of the Risk-Perception Commons: Culture Conflict, Rationality Conflict, and Climate Change. Temple University Legal Studies Research Paper. 2011–26 . doi:10.2139/ssrn.1871503. Kasser, T., Engelman, R., Renner, M. and Sawin, J. (2009) Shifting values in response to climate change. In: 2009 State of the World: Into a Warming World. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 122–125. Lawrence, F., Evans, R., Pegg, D., Barr, C. and Duncan, P. (2019) How the right’s radical thinktanks reshaped the Conservative party. The Guardian 29 October. . Lenzi, D. (2019) Deliberating about Climate Change: The Case for ‘Thinking and Nudging’. Moral Philosophy and Politics. doi:10.1515/mopp-2018-0034. Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U.K.H., Seifert, C.M., Schwarz, N. and Cook, J. (2012) Misinformation and Its Correction: Continued Influence and Successful Debiasing. Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 13 (3), pp. 106–131. doi:10.1177/1529100612451018. Miller, S. (2001) Public understanding of science at the crossroads. Public Understanding of Science. 10 (1), pp. 115–120. doi:10.1088/0963-6625/10/1/308. Niemeyer, S. (2014) A defence of (Deliberative) democracy in the anthropocene. Ethical Perspectives. 21 (1), pp. 15–45. doi:10.2143/EP.21.1.3017285. Nilsson, A., von Borgstede, C. and Biel, A. (2004) Willingness to accept climate change strategies: the effect of values and norms. ournal of Environmental Psychology. 24 (3), pp. 267–277. Oreskes, N. (2004) Beyond the Ivory Tower: The scientific consensus on climatic change. Science. 306 (5702), pp. 1686. doi:10.1126/science.1103618. Oreskes, N. and Conway, E.M. (2010) No title. Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming. Petersen, A.M., Vincent, E.M. and Westerling, A.L. (2019) Discrepancy in scientific authority and media visibility of climate change scientists and contrarians. Nature communications. 10 (1), pp. 3502–3514. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-09959-4. Plehwe, D. (2014) Think tank networks and the knowledge-interest nexus: The case of climate change. Critical Policy Studies. 8 (1), pp. 101–115. doi:10.1080/19460171.2014.883859. Poortinga, W., Spence, A., Whitmarsh, L., Capstick, S. and Pidgeon, N.F. (2011) Uncertain climate: An investigation into public scepticism about anthropogenic climate change. Global Environmental Change. 21 (3), pp. 1015–1024. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.03.001. Ripple, W., Wolf, C., Newsome, T., Galetti, M., Alamgir, M., Crist, E., Mahmoud, M. and Laurance, W. (2017) World Scientists’ Warning to Humanity: A Second Notice. Bioscience. 67 (12), pp. 1026–1028. doi:10.1093/BIOSCI/BIX125. Ripple, W.J., Wolf, C., Newsome, T.M., Barnard, P. and Moomaw, W.R. (2019) World Scientists’ Warning of a Climate Emergency. BioScience. doi:10.1093/biosci/biz088. Weber, E.U. and Stern, P.C. (2011) Public Understanding of Climate Change in the United States. American Psychologist. 66 (4), pp. 315–328. doi:10.1037/a0023253. Whitmarsh, L. (2011) Scepticism and uncertainty about climate change: Dimensions, determinants and change over time. Global Environmental Change. 21 (2), pp. 690–700. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.01.016. Wilkinson, C. and Weitkamp, E. (2016) Creative research communication: Theory and practice. Manchester: Manchester University Press.  My hand is being ever-so-slightly electrocuted by poorly-earthed taps as I fend off my daughter from the broken shower cubical with my foot. She slides around the floor adding a good coating of wet bathroom grime to her layers of dust and stuck on food. She has sand in her mouth and grass in her hair. Her clothes are filthy. I too am covered in dust and dried on sweat. My hair, which I have failed to find time to wash, has semi-solidified into a permanent pony-tail. Fieldwork in Botswana has challenges. Attaining any sense of cleanliness for more than a few minutes remains one of them. Add a 10 month old baby into the mix and you may as well give up on ever being clean. Still, we at least have running water, something that in field seasons pre-baby would have been a luxury. And, thanks to a ‘returning carer’s’ fund from the University, I am not in a tent. Combining baby rearing with saltpan-drilling in Africa is not entirely without risk and in a moment of weakness, two days before we left the UK, I was genuinely considering next day delivery on ‘snake repellent’. Through suburban Oxfordshire tinted spectacles, the Kalahari is chock full with dangers. There are scorpions in the wood she likes to throw about, venomous spiders in the little holes she loves to poke her fingers and a lot of chat about widespread outbreaks of Malaria after a particularly wet year in Botswana. But I am lucky to be surrounded by friends (most of whom have small children) who not only live perfectly safe, happy lives amongst the mosquitos, snakes and dust but who thrive here on the space and the sunshine and the proximity to wildlife we just don’t have the privilege of being around in our very dull, very English little village in Oxford. Their children grow up culturally colour-blind, unafraid of bugs and beasts, of getting grubby in the dust and mud. They watch crocodiles and hippos from their gardens and somehow the inherent understanding that we are part of that big beautiful ecosystem that spreads out into the distance from their garden gates seeps into their little hearts and stays with them forever. It is a life I aspire to. And so we ignored the comments, left the largely useless snake repellent in the online shopping trolley and arrived in Botswana with enough stuff that we could probably have kitted out a small army of Botswanan babies for a year. From my daughter’s perspective, this world is magical. In the mornings we watch the dog chase the village chickens, she plays drums on the camping tupperware with the University of Botswana students and digs endless holes in the sand with her hands. We hang out with habituated meerkats, watch the bushbabys leaping through the trees before bedtime and if we’re very lucky we meet big grey elephantine giants munching their way through the Mopane. Some days she stays with Unami, our nanny in the local village, and some days she comes into the field with us where she rearranges the sampling tubes and reads the Munsell colour chart upside down and backwards over and over again. When I’m busy working, colleagues take it in turns to sing and read with her and, mostly, she loves it – babbling and giggling, pointing out birds and trees and trying, somewhat unsuccessfully, to be helpful. There are tears too of course – the burning sun and spikey Kalahari grass mean she is confined to the covered area we have rigged up between two trucks. She’s always been unimpressed by incarceration of any kind and sometimes, the days are just too long for a tiny, teething human. The trip is not without its emergencies – I lost the charger to my tablet and in my world long car journeys without the Teletubbies rank alongside extreme psychological torture. She hates the car and lone, long-distance driving around Botswana without Tinkywinky, Dipsy, Lala and Po filled me with fear and dread. Two of my colleagues drove several hours to search the electronic junk shops in Nata for a replacement charger – I will forever be eternally grateful. It’s hard to be a fully functioning part of the team – some days we must, frustratingly, stay in the village whilst the others go out into the field to overnight in less travelled corners of the Makgadikgadi. I am snot-green with envy but, at least I am here and I am able to bounce ideas back and forth with them when they arrive back from their adventures into the unknown. On other days I was unglamorously confined to the back of the truck with a bottle and breast-pump as we bounced somewhat comically over beach ridges arguing about how the landscape evolved to the melodic hum of a Medela milking machine. My contribution to cooking and washing up this year was also woefully non-existent as I battled to get my daughter fed, cleaned and asleep. Sometimes I never made it to dinner at all. But to my relief (and perhaps surprise) no one ever made me feel like a burden or an inconvenience. No one raised their eyebrows or whispered under their breath. In truth, I think even the least likely of the team seemed, in the end, to quite like having a small dribbling, giggling midget around, lowering the tone and generally keeping things real. I’m sure there are other scientists out there who might have to take their kids on fieldwork or to conferences to keep doing their research. I hope their colleagues and institutions can be as positive and supportive as mine. It is tough enough to be a scientist and a parent – the nights are long, the workload is large and the days between nursery drop-offs and pickups are short. To be further isolated from the rest of the scientific community is enough for many brilliant young women (and men) to lose the momentum and the motivation to carry on. I am certainly not sure if I will make it. I hope by the time my daughter grows up there will be more money in the University pots to offer the practical and financial support to keep women scientists in the career they chose. In the meantime, it helps a lot if you just manage not to raise your eyebrows and tut under your breath. I am extremely grateful to my family (especially Andrew), my friends and my colleagues in Botswana and Oxford for helping me get back out to the field. You all rock. Long may our adventures in science continue.  Back when I was the size of a small hippopotamus, one of my research-funders suggested I write a blog about the challenges of being a scientist and a mother. Good idea I thought. Since then, there have been approximately 4 minutes to think about this ever again. The rest of the time I’m so busy trying to be a mother and a scientist there is barely time to wash or eat. Written in the small solitary hours between short sleeps, this is my two-pence worth on the subject for now.  Fieldwork in Botswana, 8 months pregnant. Fieldwork in Botswana, 8 months pregnant. I spent my last hours before going into labour in a sediment lab with a lake core. I hadn’t really prepared well for becoming a mother and it was a bit like finding myself as an unwitting participant in an Ironman competition with only the NCT pamphlet and handbag full of water-wipes to get to the finish line. Without my friend Susie, who emptied the contents of her loft (Moses basket and all) on to our hallway a few weeks before my daughter arrived, the baby may well have been wearing an old cardigan and sleeping in a cardboard box. Thanks Sooz! At the time of writing I’m 6 months in to motherhood, I have a wardrobe defined by decorative drool, enough plastic crap to keep open a petrochemical plant and this evening, there was a poo on my bathroom floor. My particular 6-month-old gremlin also likes to wake up every night…...every…..single…..hour. She is, it seems, inured to exhaustion and goes about her day with great enthusiasm, smiling at me, the dog, random strangers in the street and inanimate objects around the house. Her zest for life is infectious and adorable and, as another science mum pointed out, an impressively effective evolutionary survival tactic. I’m late to the parental party. Whilst I was swanning around Africa doing science stuff I watched from the side-lines as my friends crossed over to the dark side and then emerged from maternal Mordor, battle-hardened, grey-haired and smug with survival as they edged towards the school gates. I was prepared for the sleeplessness, for the hours spent cleaning up poop and vomit, I was prepared for the isolation, for the loneliness at the 3am wake up when the gremlin demanded I get up for the 5th time that night. What I wasn’t prepared for was the boredom, or the loss of identity, or the deep sense of injustice as I watched the career I loved dribble away and the gulf between what was expected of me and what was expected of my partner widen to an un-crossable breadth. (Beware the bitter rage of a woman who hasn’t slept for longer than 2 hours in a row for 6 months - never complain to this particular type of human that you are ‘tired’). Most of all, I wasn’t prepared for the enormous acreage of love I would have for the pooping, drooling, sleep-terrorist. I had little idea about the gut-wrenching guilt that derives from being at my desk with data for even 1 day a week while she hangs out with (read - screams at and tries to scratch the eyes out of) well-meaning strangers at nursery. It doesn’t help that I appear to have produced the world’s most stubborn small human who refuses to eat, sleep or poop unless her mother, very specifically, is within boobs-reach. In the harsh reality of even the best-intentioned academic institution, you can paint yourself platinum and gold with Athena swan awards for all Biology cares, it gives not one shit about gender equality. I would love my daughter to grow up believing that she could be anyone and do anything she liked – pilot, fireman, farmer, accountant, explorer. After all, I’d always believed it for myself. I chose Quaternary Scientist*. I clearly hadn’t thought this through. What exactly, when I bumble off into the Kalahari with a pick-axe and spade, will I do with my daughter? Is it unfair to take her unnecessarily into the wilderness? Who will look after her when I’m trying to get a 41 ton drill-rig out of the mud? Relatives frown at me, work points out that there is no university insurance company in their right mind that will insure a fieldwork baby, suddenly I see risk everywhere, guilt tugs at my shirt sleeves. This is my dream, not hers. But I am hesitant, I also don’t want her to grow up and see a mum who gave up on the things she loved at the first sign of trouble. More than that, I want to share those extraordinary experiences with her, to provide her with the opportunity to feel what wilderness is, to wonder at wide open endless desert, to know the company of 3 thousand year old trees and stare into a sky with 6 billion stars. Perhaps one of the most precious gifts I could give her would be to have a tiny glimmer of what it feels like to connect the dots in the landscape and feel utterly humbled by the history of the Earth. In the rare moments when she sleeps I stare at the hundreds of unanswered emails that have accumulated whilst I’ve been busy mushing up carrots and cleaning vomit from the carpet. I’m not quite sure where to begin. I delete the emails from Microsoft that tell me ‘Your mailbox is almost full’ and lean ever more heavily on my long-suffering colleagues. I find a ‘return to work’ fund on the University website and get excited about covering my childcare costs in the field but the criteria require me to demonstrate that my proposed funded activities are specifically for growing my career not just for maintaining it. I wonder about this. Who are these super-humans whose maternity leave ends with a push at career development? Where is the ‘clinging on by your fingernails fund’ for the sleep-deprived scientist fire-fighting their way through the 16,000 strong ‘to do’ list that has accumulated in their absence? The fundamental challenge of parental-leave from a career in science is that the march of academia doesn’t stop when you do. It bumbles on. Deadlines fly by, project goals must still be met on time, data must still be produced so that other scientists, whose careers partly depend on your efficiency, can continue. There is no maternity cover for the narrow niche in which I have carved my expertise. And so, rather than a cup of tea, daytime television and an occasional nap, I spend those precious ‘free’ maternity-leave minutes analysing text files of data. I try to write emails to the lab-tech to explain the next experiment as the cheerful gremlin unhelpfully but enthusiastically bashes the keyboard and dribbles on my lab notes. The two screens that were once so useful for passing data between software now permanently host a range of YouTube videos featuring psychedelically-animated nursery rhymes and bouncing baby animals. There are project progress meetings, unfinished papers, long-promised peer reviews. I’m officially due back at work in a month and quite frankly I’m beyond exhausted before I’ve even begun. The Gremlin looks at me expectantly, adoringly. I have never loved another human being with such ferocious protectiveness. I wonder if I will let her down. I wonder with titanic admiration about the science-mothers who made it through this bit and thrived, or at least survived parental-Mordor with all their senses intact? If this late-night ramble is anything, it is an ode to these people, a promise never to take these super-humans for granted again. It might also be a poorly justified, guilt-ridden explanation (an apology?) to my daughter for not always being able to play peeka-boo all day every day, at least not on Mondays. And maybe it’s a plea for patience, I am learning fast the art of spinning plates but bear with me, there may be a little broken crockery ahead. *I study the 2 and half million years of Earth's history.

|

AuthorSallie is a Quaternary Scientist, National Geographic Explorer, Trapnell Fellow of African Environments at the University of Oxford and a mum; though not necessarily in that order. Archives

December 2021

Categories

All

|

||||||||||||

Sallie L Burrough

RSS Feed

RSS Feed